The Long Take

Mariah Garnett and William E. Jones

Curated by Suzy Halajian

July 16–August 27, 2016

Opening Saturday, July 16, 7–10pm

A conversation between the artists will take place on Saturday, July 23, 2–4pm.

No account of the same event is ever alike. People see things differently, and their stories are affected by the variables and circumstances of any given day. Memory is heavily constructed by time.

Artists and filmmakers Mariah Garnett and William E. Jones constantly consider this. Approached as a dialogue between the artists within the exhibition space, The Long Take presents two practitioners whose respective research-based practices are rooted in experimental documentary filmmaking and investigations into archives through which they tackle gender and the truth subject in unexpected narratives. [1] Here, we witness distinct narratives unfolding into the same scene as matters of class and class conflict intersect the work and offer the propositions around which these artworks rotate.

This exhibition borrows its title from Pier Paolo Pasolini's text "Observations on the Long Take,” which reflects on the 16mm short film of John F. Kennedy’s death —"shot by a spectator in the crowd, it is a long take, the most typical long take imaginable” [2] — and advocates for montage over a subjective, single, long take. Arguing that it is impossible to perceive reality from a single point of view, Pasolini urges for many accounts of the same event spliced together and classified in a type of collage, dissolving the various points of view and creating a multiplication of presents, abolishing the present. [3]

Mariah Garnett’s desire to get close to her subjects leads her to question the truthiness [4] of the information she encounters, and to further question how history is written and conflicting narratives imagined. Often inserting herself in her documentary works, which embrace fiction as a truth-telling device, Garnett rescripts static identifications of gender and sex. She has performed roles such as porn star Peter Berlin and, most recently, her father, in the exhibition Other & Father (2016), part of a long-term study of the history of Garnett’s father, whom Garnett recently met for the first time. The reunion led her to delve into his past, and, thus, the political landscape of Belfast in the 70s, when the BBC news documentary featured her father in an extremely controversial Catholic-Protestant relationship at the beginning of the thirty-year, violent territorial conflict known as The Troubles. Garnett’s exhibition included a shot-by-shot reenactment of the footage capturing Garnett, playing her father, and Robyn Reihill, a transgender actress, playing his then girlfriend.

Garnett’s work here extends from this project. The artist’s new film, Open Letter (2016), photographs, and sculptural installation document and interpret recorded footage of large towering bonfires in Northern Ireland from the Eleventh Night — the night before the Twelfth of July [5]. The manifold project physically drives the materials (pallets and tires) and sounds of the bonfires to close proximity, implicating the spectator in the tangled celebrations. The annual Ulster Protestant celebration and street party, seen by the Protestant community as an observance of loyalist culture in the province, often turns into a riotous bad act and displays a specific reality — ethnic and sectarian violence adorned with Irish nationalist, Catholic, and more recently ISIS symbols and effigies. Garnett reframes the imagery of the recorded material for her audience and reveals the dark pasts buried inside these ceremonious acts. Their repetition only highlights these veiled stories in the present, and interlaces them with the inescapable violence of today.

The act of inspection and the deconstruction of artifice are rooted in the prolific documentary film and writing practice of William E. Jones, whose personal “ambition is to unsettle or subvert unthinking and habitual ways of seeing.” [6] The close intertwinement of desire, sexuality, and social control drives Jones’s work, while the study of the archival material and the study of the erotic often go hand in hand. [7] Similar to Garnett, Jones desires to understand his subjects — underground figures with a cult following in porn, literary, and music worlds. This interest fuels his research [8] and advances a mode of inquiry upheld by scholars, such as Bruno Latour, who rethink facts as sites of debate. [9] Jones’s project reveals that only by scrutinizing and unearthing the archive can we critique culture’s past political and social engagements. By doing so, we inevitably arrive at a multiplicity of readings of the same material.

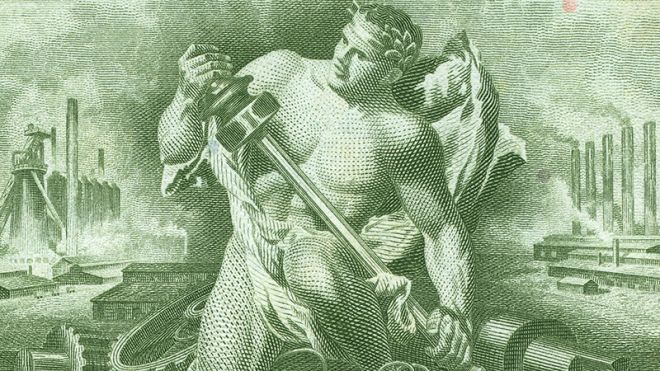

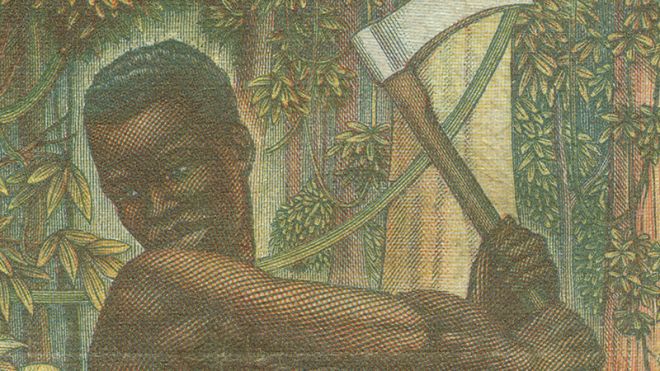

Jones’s work consists of his recent video, Model Workers (2014), and the artist’s newly conceived archival vitrine displays. The video presents an assortment of scanned banknotes from 1914–2009 that Jones has collected over the years, mainly from poor and socialist countries. Didactically projected in slideshow fashion, the notes are grouped in two sequences — the first homes in on details of bills arranged in chronological order and the second sequence consists of full views of the notes in reverse chronological order. The hypnotizing, close-up images of the engraved details expose burdened representations of physical labor. Additionally, Jones displays banknotes from socialist countries and stock certificates from the capitalist world, exhibited for the first time from his personal collection, which further emphasize the severe labor conditions that define colonial pasts and the economic realities and companies that profit from them. Sequences, both on film and paper, introduce us to allegorical figures of the masculine, hardworking, homoeroticized male laborer and the governable female laborer, religiously dedicated to harvesting the soil of the land and developing industry. Jones draws direct connections between the circulation of capital and economic development, and the “working," sexualized bodies tied to a particular class, while simultaneously laying bare the unforeseen potential spaces where decisive information could perpetually remain suppressed.

Within LACA’s exhibition and archival space, Garnett and Jones tell stories through repetition and montage, emphasizing the undying need to take a closer look and point out ambiguities and imprecisions in our historical and sociopolitical states. This personal impulse exposes the realities of exploited labor, violent class wars, and colonial struggles that are often blanketed as celebrations of progress and innovation. The artists’ undertakings assure us of the value of exposing these layered truths; they ask us to simply stay with the material.

______________________________

[1] Both artists have engaged with Peter Berlin, the notorious gay-porn icon of the early 1970s, although in strikingly different ways. In Garnett’s 2012 film, Encounters I May Or May Not Have Had With Peter Berlin, she attempts to embody Berlin by reenacting his poses in his signature style and, later, interviewing Berlin in his apartment. And in v.o. from 2006, Jones uses direct porn footage Berlin starred in to construct the 59-minute work of various segments of picture from gay-porn films produced pre-1985.

[2] Pier Paolo Pasolini, "Observations on the Long Take,” trans. Norman MacAfee and Craig Owens, October 13 (Summer 1980), p. 3.

[3] Ibid., p.4.

[4] “Truthiness” is truth measured by conviction rather than accuracy, as articulated by Carrie Lambert-Beatty in “Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October 129 (Summer 2009), p. 7.

[5] The night celebrates the victory of Protestant King William of Orange over Catholic King James II during the Revolution of 1688, which marked an important transition towards parliamentary rule.

[6] Matthew P. Carson, “William E. Jones Interview,” Monsters and Madonnas, International Center of Photography Library blog, December 20, 2010.

[7] Jones’s 2009 film work Killed is composed of black-and-white still images assembled into a 104-second loop. The artist sought examples of social life as he perused the Library of Congress’s FSA archives, but was soon led to a different kind of project by the rejected, hole-punched images he encountered.

[8] The subjects in Jones’s films and books have included artist/filmmaker Fred Halsted in Halsted Plays Himself (2011); the cult band Morrissey in Is It Really So Strange? (2004); Finished (1997) featuring porn star Alan Lambert; and Boyd McDonald, publisher of the first queer zine, Straight to Hell, in True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and Straight to Hell (2016). Garnett’s films have engaged with distinct subjects, such as U.S. war veterans who work as Hollywood stunt doubles in Full Burn (2014), and Catalina de Erauso, a nun turned conquistador from the 16th century in Picaresque (2011).

[9] Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 30 (Winter 2004), p. 231.

About the Artists

Mariah Garnett lives and works in Los Angeles. She mixes documentary, narrative, and experimental filmmaking practices to make work that accesses existing people and communities beyond her immediate experience. Using source material that ranges from found text to iconic gay porn stars, Garnett often inserts herself into the films, creating cinematic allegories that codify and locate identity. Her work has been screened internationally, including: Kerstin Engholm Galerie, Vienna, (2015); REDCAT, Los Angeles (2013); Ann Arbor Film Festival (2013); White Columns, New York (2012); Venice Biennale, Swiss Offsite Pavilion (2011); Rencontres Internationales, Paris, Madrid, Berlin, Beirut, (2011); Midway Contemporary Art, Minneapolis (2010). In 2014, she was in residence at The Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin, and featured in Made in L.A., the Hammer Museum's biennial exhibition. In 2016 she had her first institutional solo show at the MAC in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and her first solo show at a commercial art gallery in Los Angeles at ltd los angeles. Garnett holds an MFA from CalArts in Film/Video and a BA from Brown University in American Civilization.

William E. Jones is an artist, filmmaker, and writer born in Ohio and now living in Los Angeles. He has made two feature length experimental films, Massillon (1991) and Finished (1997), the documentary Is It Really So Strange? (2004), videos including The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998), and many other moving image works. His work has been the subject of retrospectives at Tate Modern, London (2005); Anthology Film Archives, New York (2010); Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and Oberhausen Short Film Festival (both 2011); and has been shown at Museum of Modern Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Musée du Louvre, Palais de Tokyo, and Cinémathèque française, Paris; Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He has published the following books: Is It Really So Strange? (2006), Tearoom (2008), Heliogabalus (2009), Selections from The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton (2009),“Killed”: Rejected Images of the Farm Security Administration (2010), Halsted Plays Himself (2011), Between Artists: Thom Andersen and William E. Jones (2013), Imitation of Christ, which was named one of the best photo books of 2013 by Time magazine, Flesh and the Cosmos (2014), and True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and Straight to Hell (2016). He recently received a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for a book on art dealer and collector Alexander Iolas.

images -main and first:

Mariah Garnett, Open Letter, 2016, (still) HD video, color, sound.

bottom:

William E. Jones, Model Workers, 2014, (still) HD video, color, silent, 12:16 min.